BLOG

On the “Predatory” Influence of our Eyes on the Taste of Wine

Gabriel Lepousez Wine Education & Careers

This article is the first of an upcoming series by French neuroscientist Gabriel Lepousez. Gabriel is part of the Scientific Committee formed by WSG in the context of its "Architecture of Taste Research Project". He has also presented a fascinating segment on "The Neuroscience of Wine Tasting" as part of The Science of Wine Tasting Webinar Series which will resume with new episodes in the Spring of 2022.

The wine tasting paradox

There is a real paradox in the experience of tasting a product like wine. Tasting is such a familiar, instinctive, and seemingly obvious act; something that we take for granted. At the same time, wine is a one of the most complex sensory objects that we put into our mouths.

Indeed, wine is one of the rare sensory objects of our daily life which solicits all at the same time:

- Our sense of vision

- Our sense of smell by the presence of aromas which are perceived by the nose via the nasal cavity (the so-called “orthonasal smell”) and in our mouth, via the back pathway connecting the throat and the nose (“retronasal smell”)

- Our sense of taste (which detects the presence of sour, bitter, sweet, salty, umami)

- Our sense of touch, which analyzes the texture of the wine as well as the temperature or the presence of spicy or irritating compounds

We could even potentially add our sense of hearing, which is solicited by the sound of a wine being poured into a glass (think of the sound of Champagne bubbles, or the gorgeous gurgle of a sweet wine being poured into a glass), the sound of the cork being pulled out of the bottle, or even the explanatory words of the winegrower and the sommelier.

In comparison with another aesthetic object such as a painting or a piece of music, wine is in a way a praiseworthy champion of complexity due to its ability to summon almost all of our senses simultaneously. Under our skull, it sets off fireworks in the form of electrical activity in multiple regions of the brain. So much so that it becomes a real challenge for our nerve cells to process such a barrage of information rushing at the same time through our different sensory channels. We don’t get a headache every time we take a sip because the brain works hard and quick to select, filter, prioritize and determine the relevancy of such information, just as it does to make a snap purchase or consumption decision - all in spite of such a sensory complexity framework.

Sensory hierarchy: How does the brain sort out wine sensory dimensions

Faced with such a multi-sensory firework, the notion of sensory hierarchy is well illustrated by the influence of vision on our perception of wine. Man is a visual animal who primarily bases his decisions on the visual information that reaches him. While losing your sight is a considered to be a disability (similar to losing your hearing), losing your sense of taste and/or smell is not usually considered as one, in spite of all the efforts of related to COVID-19 to raise our general awareness on alterations in smell and taste.

When visual information (e.g., color) conflicts with olfactory information (e.g., aroma), vision has the final word. A case in point is how the simple addition of an odorless and tasteless red coloring agent to a white wine will strongly influence the analysis of the taster to the point of using red fruit descriptors (redcurrant, raspberry) to characterize this red colored wine, even though this same white wine is normally described with descriptors such as white fruits and honey (Morrot et al., 2001 Brain Lang). This effect is also manifested in our everyday tasting comments: the use of red fruits descriptors is to a certain extent restricted to red wine. We may not consider such descriptors coherent and valid for white wine, although the example of Champagne wine made of 100% pinot noir clearly deserves our attention when it comes to red fruit.

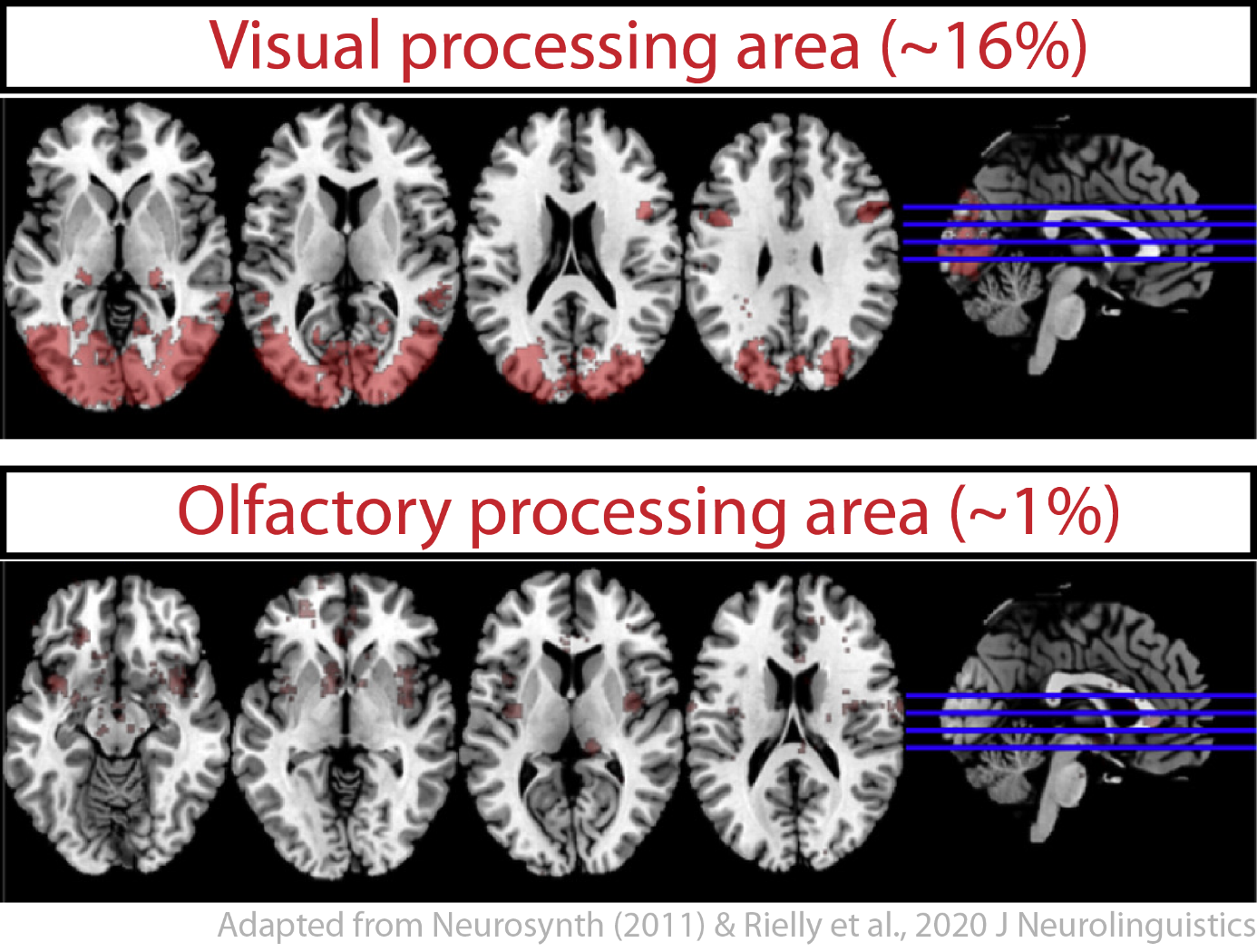

The influence of color extends to color intensity: the darker the color of wine, the more aromatically intense it will be perceived (Kemp & Gilbert, 1997). So, the moment we taste a wine, visual information can completely alter our aromatic analysis of it. How can we explain this phenomenon? First, we must understand that vision is a pre-eminent sense, and it carries a lot of weight upon all of our actions and decisions. In the brain, the area involved and engaged during the recognition of a visual stimulus represents around 16% of the surface of the cortex versus only 1% when there is an olfactory or gustatory stimulus (see Figure 1, adapted from Yarkoni et al., 2011 Nature Methods; Reilly et al., 2020 Journal of Neurolinguistics). The sense of vision is so dominant that it inhibits the other senses and monopolizes the information that will be used by our brains to make decisions and to pass judgment. Thus, studies involving brain imaging have shown that the activity in the gustatory and olfactory centers increases when the eyes are closed and decreases when visual information returns in plain sight (Wiesmann et al., 2006 NeuroImage; Xu et al., 2014 Neuroimage).

Figure 1: Brain imaging data (fMRI) showing the average functional brain activation maps (activated area are colour-coded in red) in response to a visual stimulation (top) or to an olfactory stimulation (bottom). Adapted from Neurosynth (Yarkoni et al., 2011 Nature Methods) and Reilly et al., 2020 Journal of Neurolinguistics.

In other words, closing one’s eyes for a few moments for the purpose of shunting our vision allows the brain to rebalance the different sensory channels and increase the receptivity of the olfactory and taste centers. In the face of uncertainty between smell and color (such as in the red-colored white wine experiment), vision takes precedence and guides our decision to the detriment of smell. In a kind of winner-takes-all effect, the preeminence of vision in our brain tends even to create bias and overwrite what our nose is telling us about the wine. This effect could even be reinforced during the verbalization of our impressions, given that vision has a privileged anatomical access to the language area of the brain, compared to olfaction (Olofsson & Gottfried 2015 Trends Cognitive Science).

First come, first served: how the sequential ritual of wine tasting frames our appreciation of wine

Another aspect that can explain the overriding significance of visual information in our representation of the taste of wine is sensory temporality. Indeed, we often tend to look at the wine before physically placing it in our mouth – to taste it first, so to speak, with our eyes. However, the brain is a predictive and statistical machine that uses information from past and present experiences to predict and to anticipate the future. This anticipation phenomenon is even more effective if the first information about the wine reaching our brain is a preeminent visual piece of information. As a result, our brain is “soaked” and conditioned by visual details such as color. The brain tries to predict and anticipate the taste of the wine based on this precious information by recollecting its memory of red wine. Moreover, color may create an attentional bias to selectively enhance the focus of red wine-associated aromas while inhibiting the analysis of white wine-associated flavors.

Thus, the reconstruction of a coherent picture of wine by the brain built significantly on the first framework established by preliminary visual cues. In addition to color, other visual information such as the price of a wine can influence our judgement. In a blind tasting where the only information provided about the wines is the price, such knowledge profoundly modifies the quality judgment made of the wine in question. Experience has shown that a wine that is tasted blind except for an announced price of $90 will be scored higher or appreciated more than a sample of the same wine with an announced price of $10 (Plassmann et al., PNAS 2008). In the end, all these results uncover the importance of the temporal order of sensory events in wine tasting and how each piece of sensory information can influence the interpretation of each one.

Geo-sensory tasting: in the quest of a new tasting method

During a classical analytical tasting, the protocol usually invites the taster to look first at the wine, then analyze the nose and then confirm its impressions in the mouth. When performing such eye-nose-mouth temporal sequence, all the numerous and dynamic sensations in the mouth —gustatory, tactile, trigeminal, retronasal— are thus biased and “contaminated” by the preceding events or at least relegated to the back row for just a “confirmation” of the first picture. This natural tendency to confirm previous elements is all the more important that such “confirmation bias” is a well-known cognitive bias, a form of hardwired and subconscious thought mechanism that automatically leads the brain to reinforce more information that confirms preexisting beliefs. Given the unique richness of the sensations that emerge in the mouth, this stage deserves more than being just a final step to confirm in the mouth the aromas identified in the nose.

How to re-equilibrate the tasting sequence and escape from this “confirmation bias”? One approach would be to simply invert the classical eye-nose-mouth sequence and to start with the mouth. In a mouse-nose-eye sequence, the brain first gets a native and holistic picture of the harmony between taste and textures on the palate, quickly followed by retro-nasal olfaction, without any influence from preliminary information and without any temptation to “confirm” those preliminary elements. Interestingly, such a method has been the practice of the professional gourmets in the 15th-16th centuries, who were in charge of ensuring the origin of the wines they were selling. For this taste certification, they practiced their version of geo-sensory tasting with an opaque shallow silver cup called a “tastevin” in dark cellars using only candlelight. In the absence of transparent tulip glasses, the use of an opaque cup guides the tasting to first take a sip and focus on the global taste and mouthfeel sensations, followed by retronasal smelling and lastly on the color and clarity of the wine that could be only appreciated when getting close to the candlelight. Nowadays, tasting in a cup is still the standard reference for the tea or sake tasting. These observations illustrate how the design of the tasting vessel can profoundly format the tasting method and change the focus of our attention.

In praise of blind tasting

Another approach to reduce the invasive influence of visual information in the tasting analysis would be to simply taste blind in the dark or in a opaque glass in order to shield the tasters from the predatory influence of visual elements. It has become a reflex for many tasting professionals to close their eyes while tasting and may explain why blind people have better performance in olfactory identification (Rombaux et al., 2010 NeuroReport). Moreover, aroma judgements on a white wine that was colored-dyed red were more accurate when the wine was presented in opaque glasses rather than when presented in clear glasses (Parr et al., 2003 Journal Wine Research). Interestingly, such a mere and playful experience may turn into an uncomfortable situation for some tasters, as some people becoming slightly anxious to taste an object which they cannot identify at first with their eyes. In the same train of thought, would you accept to eat in the dark, a striking experience that has been popularized by some restaurants since 2000’s. Although feeling uncomfortable during a wine tasting is not a desirable option, such an experience may be decisive not only to understand the weight of vision in the taste of the wine, but also to reveal to what extent closing our eyes can enhance our sense of taste and smell.

While tasting with a black opaque glass, I would also argue for a second benefit: not being able to see the wine color will give you the freedom to mentally explore some facets of the wine that would have been otherwise hidden by the preliminary knowledge of the color. Let’s come back to this 100% Pinot Noir Champagne wine: in an opaque glass, you have a complete freedom to imagine this wine as being a rosé wine and to taste the wine from this perspective. You can then mentally switch to a “white wine” tasting mode and explore the aromatic landscape of the wine from this new angle. Thus, in a paradoxical manner, the absence of visual information may free your brain to consciously explore the different facets of the wine rather than being unconsciously framed by the color. Only in the end, you still have the freedom to look at the real color of the wine by pouring the wine into a transparent glass and starting a second classical analytical tasting. Two tastings for the price of one – here’s an offer you can’t refuse.

This article is the first of an upcoming series by French neuroscientist Gabriel Lepousez. Gabriel is part of the Scientific Committee formed by WSG in the context its "Architecture of Taste Research Project". He has also presented a fascinating segment on "The Neuroscience of Wine Tasting" as part of The Science of Wine Tasting Webinar Series which will resume with new episodes in the Spring of 2022.

More about the Architecture of Taste Research Project